[Updated 4/18/12, 8:51 p.m. See below.]

When the Mt. Elliott Makerspace, the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition, and Detroit Future hosted a DiscoTech event at the Museum of Contemporary Art last weekend, it was a uniquely Detroit affair. As kids and their grown-up escorts bounced between stations that offered lessons on everything from beat-making and computer anatomy to custom bike-building with the East Side Riders and stenciling, a DJ spun records in the background. Anthology Coffee’s pop-up cafe served up snacks to a crowd that was decidedly less monochromatic (read: white) and male-dominated than those usually found at tech events in Detroit. By the time I arrived, midway through the activities, 154 attendees had been counted by the women occupying the information table—not bad for an unseasonably warm Sunday afternoon.

If the Mt. Elliott Makerspace’s founder, Jeff Sturges, has his way, an increasing number of Detroiters will benefit from the energy building behind the makerspace movement as a way to develop urban space and foster entrepreneurial experimentation in communities like Detroit, whose educational and economic challenges are well known. Sturges says makerspaces are a way to concentrate public and private resources to make Detroit a fertile ground for raising the next generation of innovators.

After all, Sturges points out, the maker ethos has always flourished in this city of genius tinkerers, whether we’re talking about Henry Ford and his Model T, Berry Gordy birthing an entire, game-changing genre of music out of a tiny house on Grand Boulevard, or hip-hop superproducer J Dilla hacking his MPC to make beats that, six years after his death, continue to sound 20 years ahead of their time.

“I believe that we’re beginning to understand that most of the maker-innovators like Thomas Edison and Steve Jobs became so only partly because of their traditional schooling,” Sturges says. “These leaders were exposed to talented mentors, passion-fueled experiences, and environments where they were able to repeatedly experiment and fail—and eventually succeed.”

The Mt. Elliott Makerspace is located on the city’s east side, in the basement of the Church of the Messiah, which has its own all-inclusive mission of community empowerment. Sturges, a Boston-area native who formerly worked at the Sustainable South Bronx Fab Lab, wanted to replicate the MIT Fab Lab model on a smaller, cheaper scale in Detroit. The Mt. Elliott Makerspace is supported by the Kresge Foundation, Volkswagen, Re:Source Partners, Make magazine, and a group of volunteers and mentors drawn from the local business, tech, and university communities. [Paragraph updated to clarify supporting entities.]

Sturges estimates that in the two years the makerspace has been in existence, it has exposed 10,000 Detroit kids to the possibilities contained in technology and entrepreneurship through its church-basement headquarters, a booth at Eastern Market, and regular “open hack” events. “It’s sort of laughable what I thought we’d do at first,” Sturges says of the makerspace’s early days. “I thought we’d basically make farm tools. A lot if this is very experimental—rarely have our workshops gone exactly as planned.”

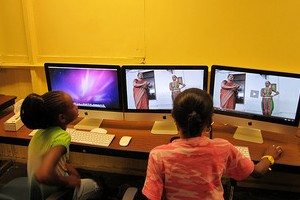

Instead, the Mt. Elliott Makerspace now has four concentrations: transportation (powered by human strength and alternative energy), electronics (tools and systems that involve electricity and electronics in their operation), digital tools (computers, robotics, software, programming, audio/visual production, social networks), and wearables (screen printed clothing, accessories, embroidery). The makerspace has both earn-a-bike and earn-a-computer programs, where people are taught basic repair skills in exchange for a used bike or computer. Sturges plans to open computer and bike repair shops soon to help train people not only in technical skills but entrepreneurship.

The Mt. Elliott Makerspace also has a woodshop that was built by a retired machinist using recycled lumber and windows. The windows allow those working on IT projects to observe those in the woodshop, and vice-versa—an

important feature, Sturges notes, in preventing work silos and fostering innovation born from multidisciplinary creativity. In the future, Sturges plans to add concentrations in food (farming and preparation), design (2-D and 3-D CAD), music, and arts. But his main goal is building capacity and communities of knowledge. “We want people to keep coming back so they can teach the next group,” Sturges says. “We’re probably casting a net that’s a little wide, but it’s important to have communities of expertise.”

Sturges is also facilitating the creation of other new makerspaces in Detroit. Drawing inspiration from the open-source idea in software and hardware, he wants to share the Mt. Elliott Makerspace model so that it can be adapted and improved upon by others. Right now, he has three additional sites in mind: the HYPE teen center inside the main branch of the Detroit Public Library, Detroit Community Schools in the Brightmoor neighborhood, and 5E Gallery in Southwest Detroit. Partial funding commitments are already in place or pending through Cognizant’s “Making the Future” initiative as well as CEOs for Cities and the Knight Foundation.

Sturges says that, in addition to teaching technical and entrepreneurial skills, makerspaces build persistence and courage. Spending time in one, he says, affects how you approach life. “It’s an environment where people feel cared for,” he adds. “People often look at a challenged community and want to bring in arts programs. This speaks more to job skills and creative problem-solving. There are lots of people here to help push you along.”